Download (PDF)

BRIEFLY

Semiconductors are the building blocks of almost every modern technology, from dishwashers to smartphones to javelin missiles. Shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic, along with rising geopolitical tensions in the region where most chips are produced, have highlighted the fragile supply chains of this critical technology. In response, US policymakers have invested billions in the domestic production of this critical technology, through incentives to semiconductor manufacturers and investments in US research and development. Nearly two years on from the start of this effort, as incentives continue to be awarded, policymakers can raise the likelihood that the US achieves greater security in the semiconductor supply chain by (1) continuing to award incentives to facilities located in high-talent areas, (2) allowing highly skilled foreign workers to fill in-demand positions, and (3) following through on announced investments in the domestic STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) talent pipeline.

WHAT TO KNOW

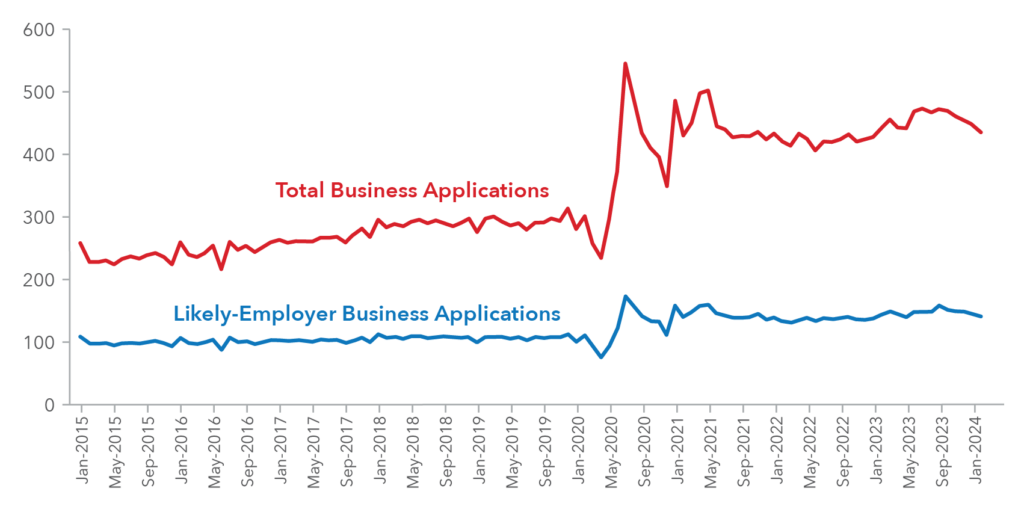

Over time, both global competition and the economies of scale that characterize modern chip manufacturing have resulted in a concentrated and fragile supply chain. From 1990 to 2020, the global share of semiconductors, or computer chips, produced in the US fell from 37 percent to 10 percent. Today, countries in East Asia account for 73 percent of total semiconductor production capacity, and that region manufactures nearly all of the most advanced chips needed to run the newest technologies. Indeed, in 2020, only two companies—South Korea’s Samsung and Taiwan-based Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) —could manufacture leading-edge “logic” chips that process data in devices like tablets and smartphones. During the pandemic, increased demand for consumer goods caused shortages among both advanced and older-model legacy logic chips (such as those found in cars). Those shortages, coupled with rising prospects of tensions with China over control of Taiwan, have spurred efforts to rebuild America’s capacity to manufacture semiconductors domestically.

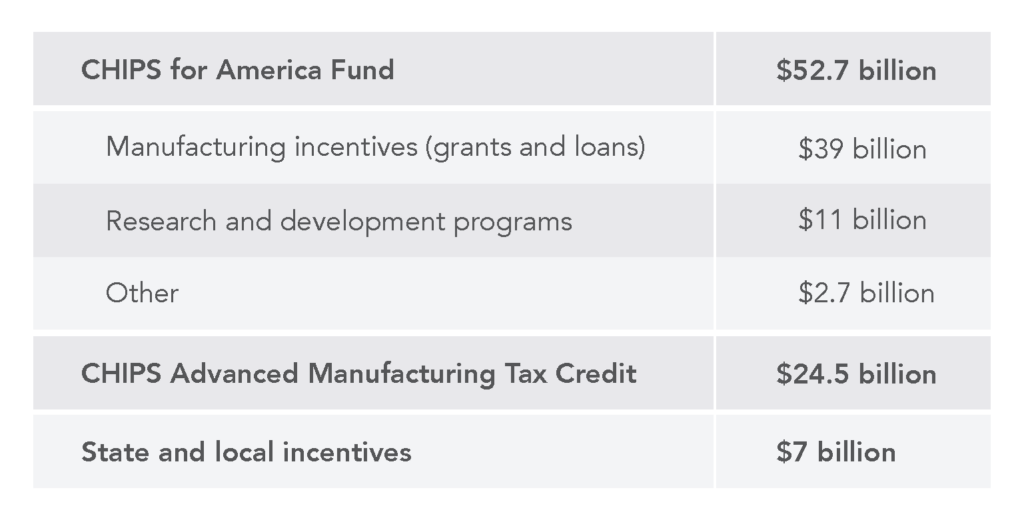

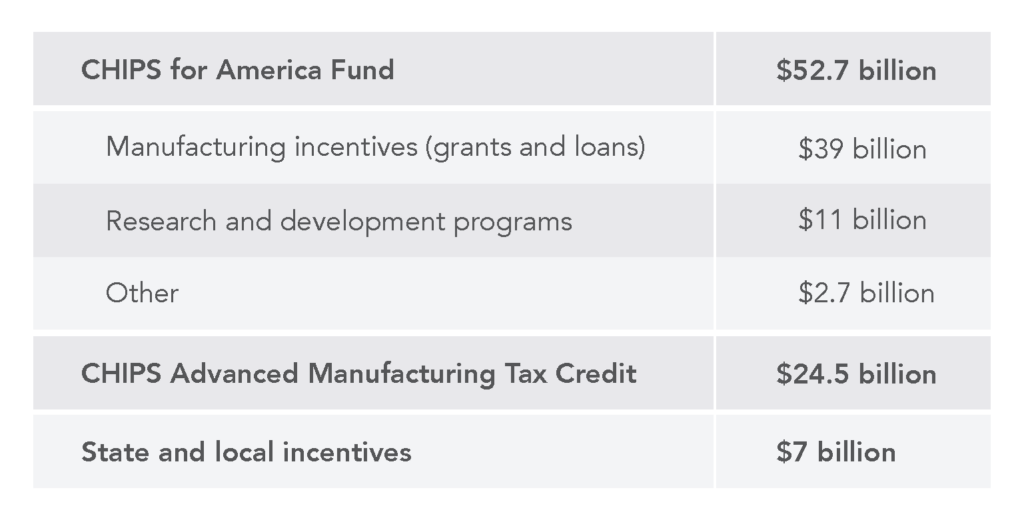

The 2022 CHIPS (Creating Healthy Incentives to Produce Semiconductors) and Science Act aimed to rebuild the country’s semiconductor manufacturing capacity and increase investments in long-term research-and-development pipelines. The law includes $52.7 billion in appropriations to bolster the semiconductor industry through 2026, among them $39 billion earmarked to incentive firms to build chip facilities in the US, and $11 billion earmarked for investment in advanced-chips R & D. The CHIPS Act also created an Advanced Manufacturing Tax Credit, intended to encourage private-sector investment in the industry; the Congressional Budget Office projects this credit will cost $24.5 billion. On the heels of the CHIPS Act, state and local policymakers have announced an estimated $7 billion in additional incentives to attract semiconductor facilities to their cities and states. In total, leaders from the local to the federal levels have devoted $84.2 billion to incentivize domestic chip manufacturing.

Table 1: An estimated $84.2 billion in public funds have been directed to spur US semiconductor production across federal, state, and local efforts

Source: CHIPS for America and tax credit funding from Congressional Research Service (2023). State and local incentives from the Tax Foundation (2024).

Note: Included in “other” spending in the CHIPS for America Fund is $200 million for CHIPS-related workforce development, $500 million for information and communications technology security, and $2 billion for defense-related semiconductor manufacturing.

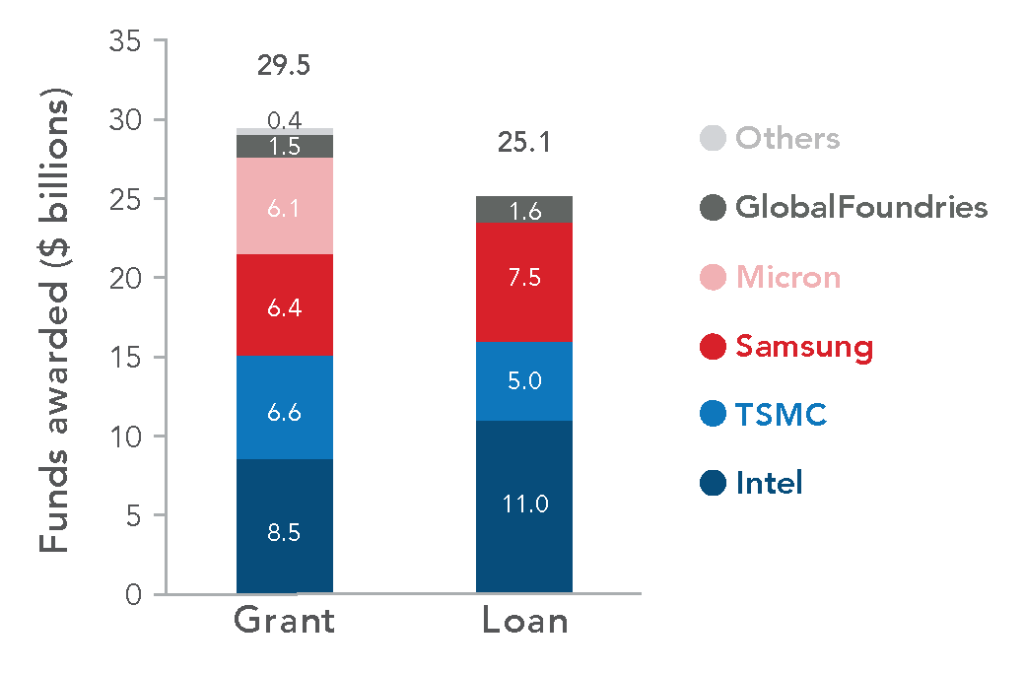

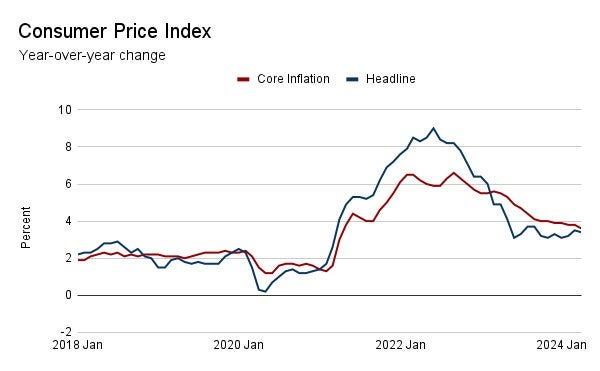

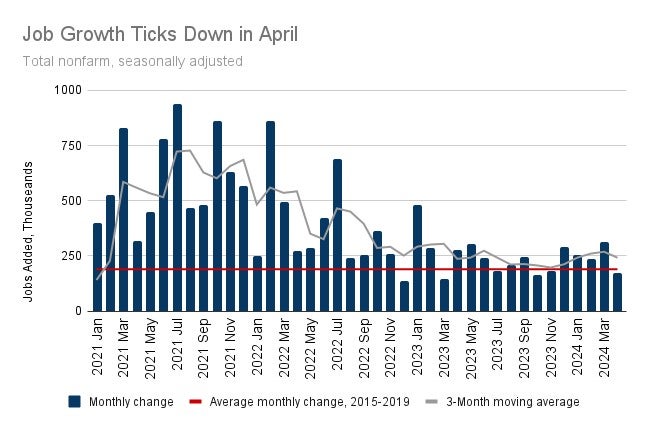

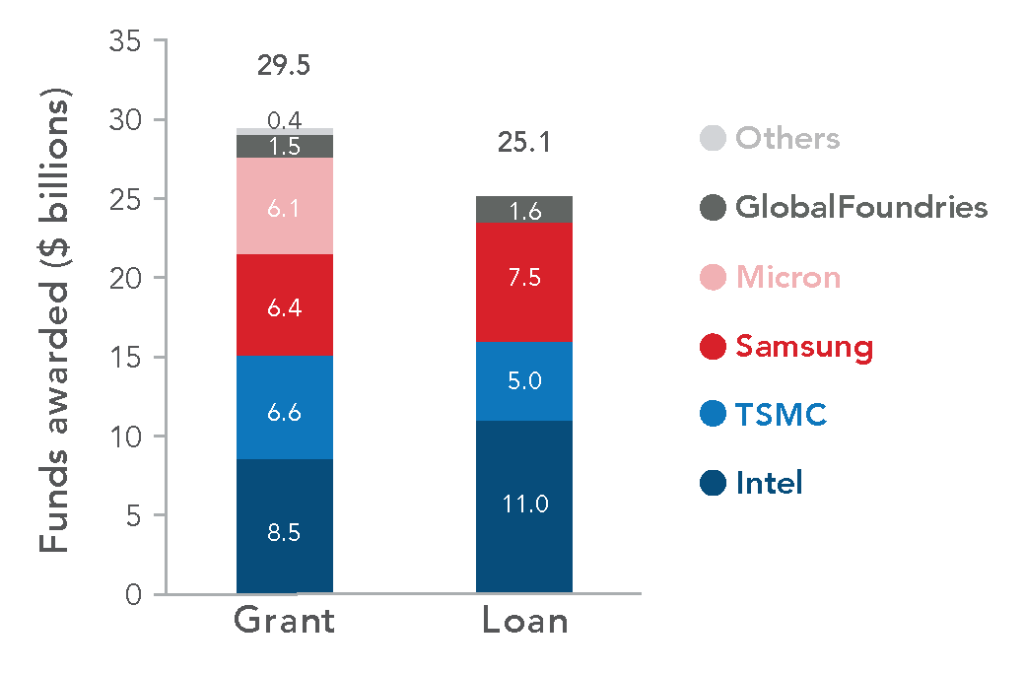

Nearly two years after the passage of the CHIPS and Science Act, $54.4 billion in grants and loans have been awarded to semiconductor manufacturers. The Department of Commerce’s CHIPS for America Program Office posted its first Notice of Funding Opportunity for incentives to build chip manufacturing facilities in February 2023. Producers seeking awards in the form of grants or loans have been submitting applications for funds on a rolling basis, with the first award announced in December. As shown in figure 1, $29.3 billion in grants and $25.1 billion in loans have been announced through May 2024. Incentives awarded to GlobalFoundries, Microchip Technology, and BAE systems are aimed at building legacy chips. The US-based technology company Intel, a longtime chipmaker that has fallen behind foreign competition in recent years, has received the largest share of grants and loans for both legacy and leading-edge chip production. Finally, TSMC was awarded a combined $11.6 billion in grants and loans to produce among the world’s most advanced chips in a new Arizona facility.

Figure 1: $54.6 billion in federal CHIPS manufacturing incentives have been awarded

Source: “Other” grants were awarded to Absolics, BAE Systems, Microchip Technology, and Polar, totaling $392 million. Funding data as of May 29th, 2024.

Note: Semiconductor Industry Association (2024a) 3390.

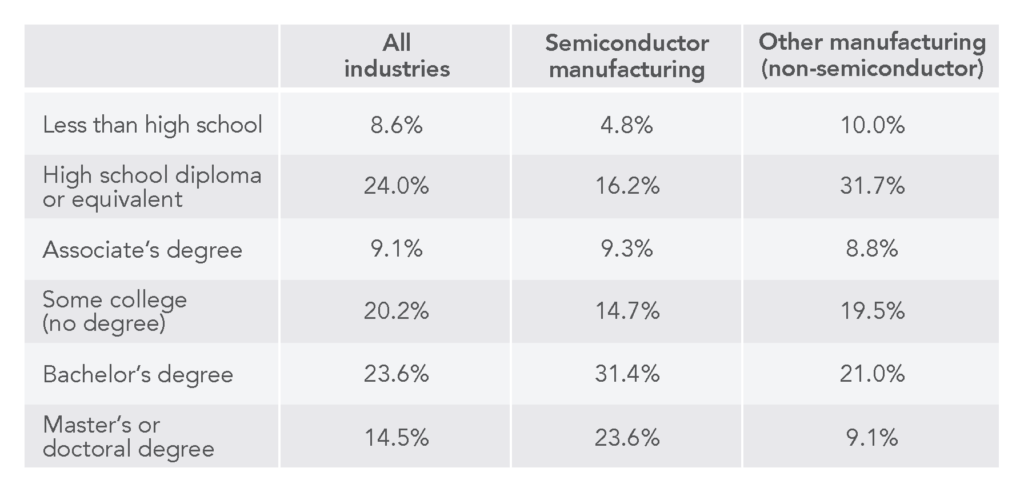

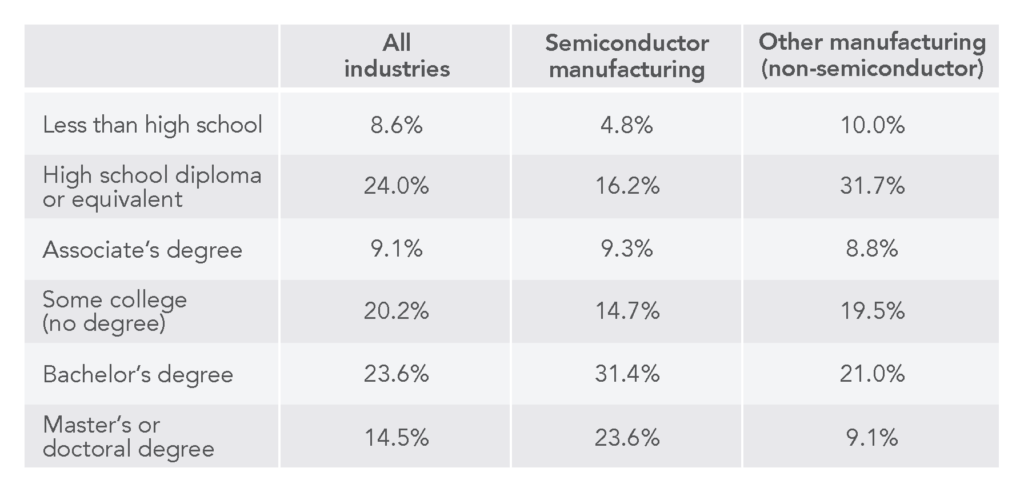

Table 2: Workers in semiconductor manufacturing are more likely to have a BA or advanced degree than workers in other industries

Source: American Community Survey (2022), via IPUMS.

Note: Semiconductor manufacturing workers are identified as those listed under NAICS codes 3344 and 3346.

As funds are allocated and production facilities are built, one of the most important undertakings will be to ensure that there is a supply of skilled workers able to fill these roles. The domestic semiconductor manufacturing workforce, numbering about 203,000 today, is expected to grow substantially as a result of policymaker efforts. The Semiconductor Industry Association estimates that about 115,000 domestic jobs will be added across the design and manufacturing of chips.

These design and manufacturing roles are highly technical and require specific training. Production of chips requires skilled machinery operators, electrical engineers, and materials science PhDs, among others, with training that ranges from 2-year degree programs to PhDs. As shown in table 2, workers in the semiconductor industry in the US today are more likely to have associate’s degrees, bachelor’s degrees, and master’s or doctoral degrees compared to both the entire workforce and other manufacturing sectors.

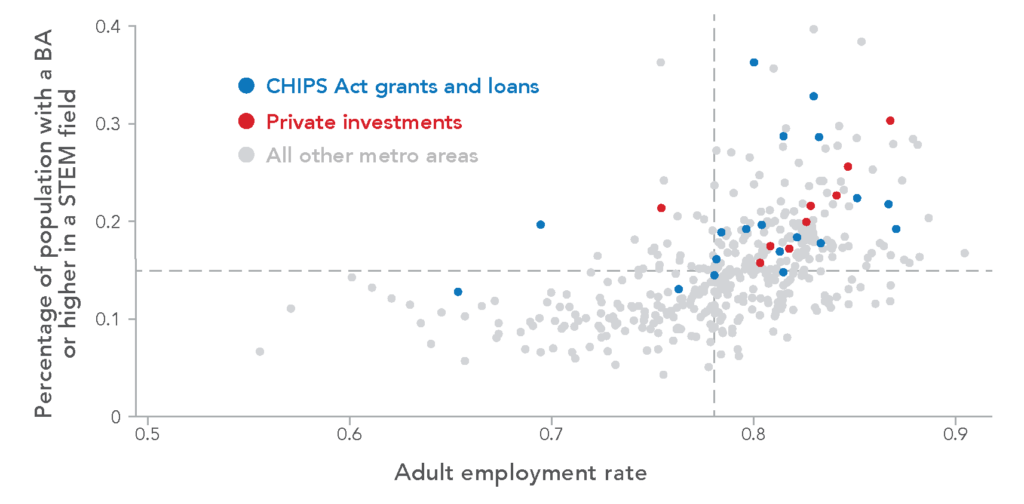

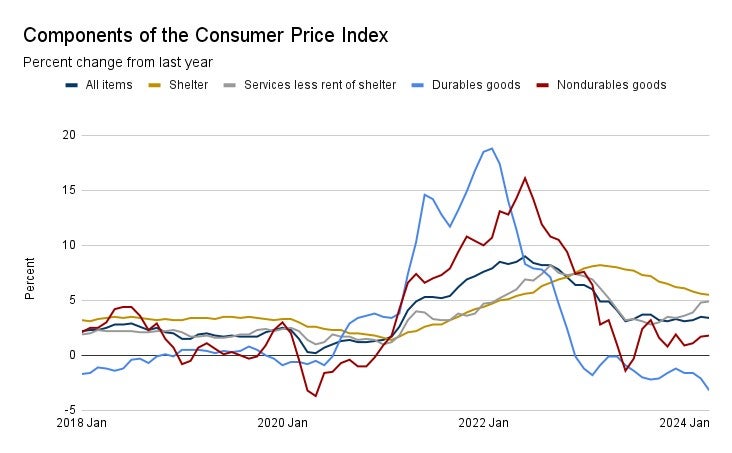

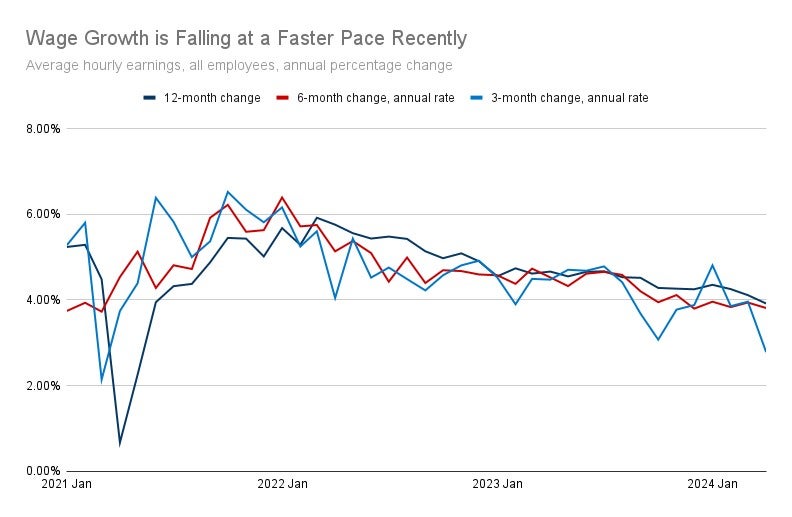

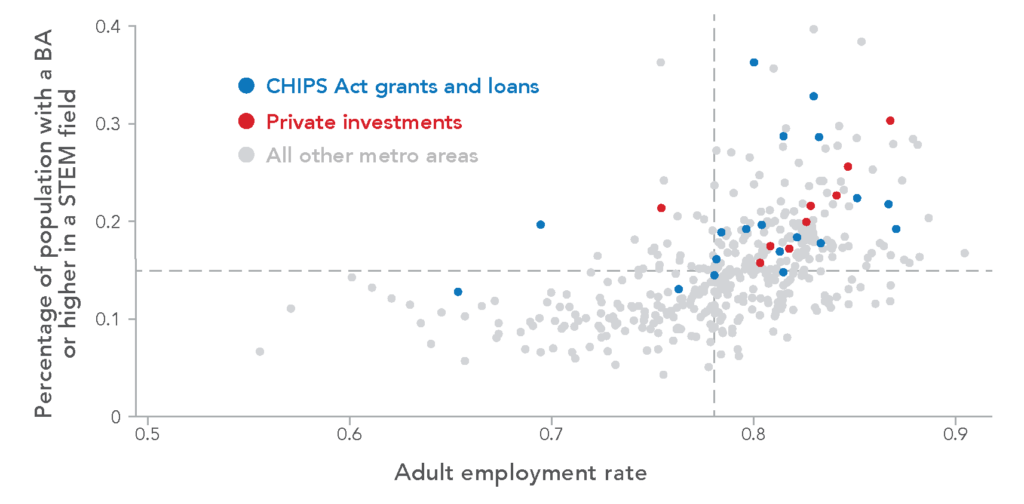

First, given the specific goals of this effort and the high level of skill required for semiconductor manufacturing, advancing the chip industry is more likely to be successful if facilities are located near skilled workers who can meet these firms’ needs. The CHIPS and Science Act has been viewed by some as the centerpiece in a new strategy of “place-based industrial policy,” in which policies intended to stimulate critical sectors can also revitalize distressed communities. The tension between these two goals of place-based industrial policy—advancing highly specialized manufacturing and promoting economic development—is evident in figure 2. This figure plots US metro areas by their prime age employment rate (a higher rate is indicative of less economic distress) and the share of all adults 25 and older who have a BA or greater in a STEM field (a higher share is an indicator of a more skilled local workforce in that area).

Figure 2: CHIPS investments are primarily being made in areas with above-average STEM talent and above-average employment rates

Source: Employment rates and portion of population with STEM degrees from US Census Bureau American Community Survey Summary Tables (2024a and 2024b); CHIPS awards and private-investment announcements from Semiconductor Industry Association (2024a and 2024b).

Note: Dashed lines indicate the average of employment rates and STEM degrees across metro areas. The data underlying this graph can be downloaded here.

There simply are very few distressed local economies that are likely to have a sufficiently skilled workforce to meet the needs of manufacturing firms—that is, that lie in the upper left quadrant of the chart. To be sure, as Tim Bartik laid out in a recent AESG policy paper, policymakers have a menu of options at their’ disposal for investing in local economies, but conflating the goal of rebuilding semiconductor manufacturing with that of raising community development is unlikely to achieve either aim.

Figure 2 identifies both federal awards and private investments in chip manufacturing so far (in blue and red, respectively). These investments tend to be in areas with both high STEM talent and above-average employment rates. Indeed, many funding announcements are set to expand production in existing manufacturing clusters, such as Arizona’s “Silicon Desert.”

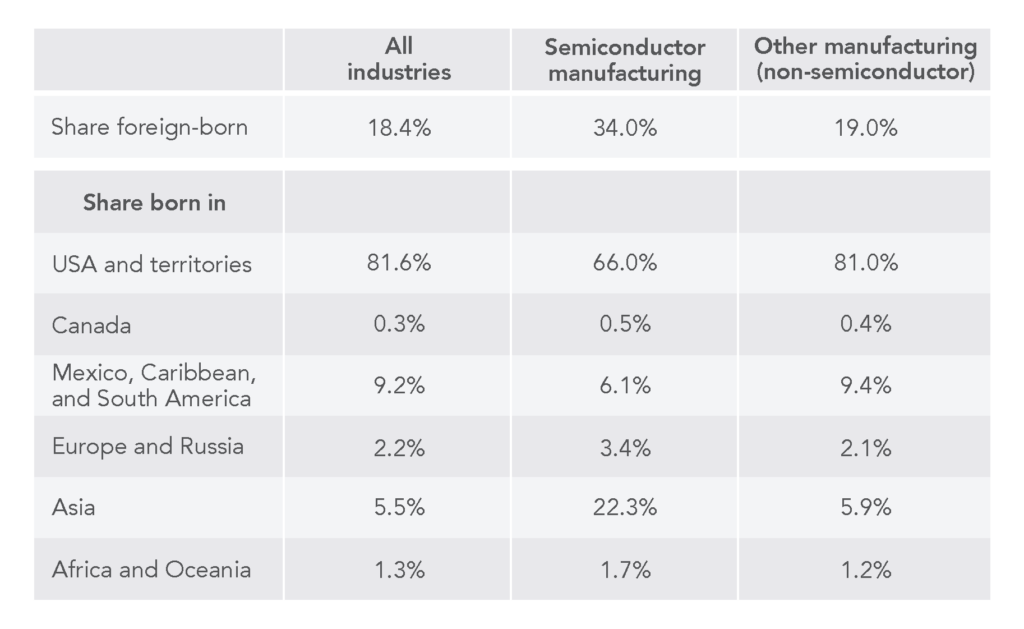

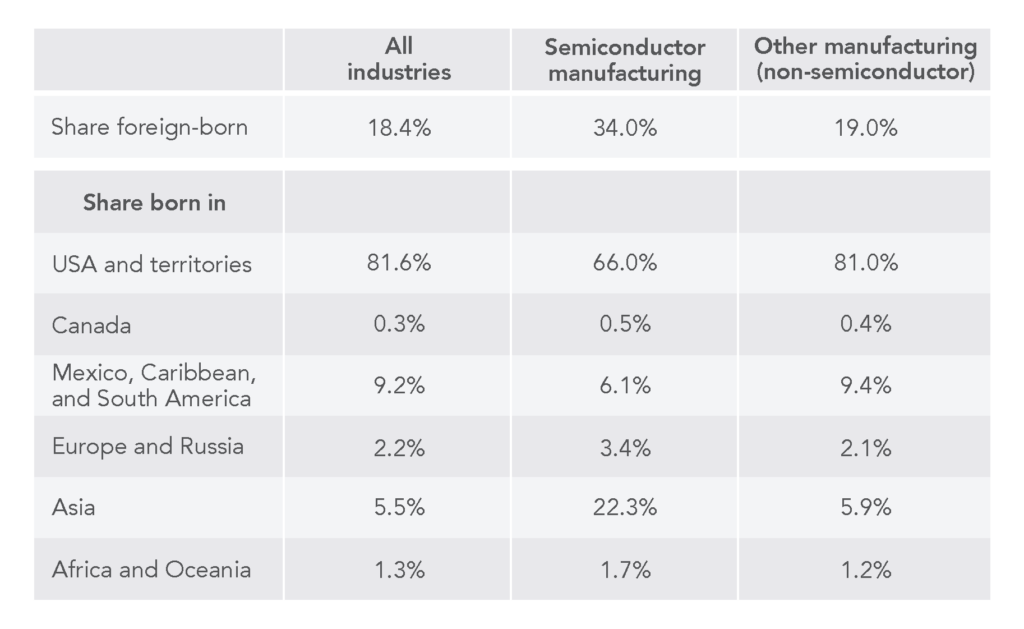

While firms locate investments in high-talent areas, policymakers should facilitate high-skilled immigration, particularly among workers with experience in the semiconductor industry. Immigration reform is perhaps the lowest-hanging fruit for quickly raising the supply of talented workers. As displayed in table 3, over one-third of workers in the semiconductor industry (34 percent) are foreign-born, more than double the share across the workforce (18.4 percent).

Table 3: Over one-third of workers in semiconductor manufacturing are foreign-born

Source: American Community Survey (2022) via IPUMS.

Note: Semiconductor manufacturing workers are identified as those listed under NAICS codes 3344 and 3346.

Analysts at Georgetown’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET) estimate that staffing new chip facilities will require 3,500 new foreign workers. While many of them could move from other industries or come from US universities, allowing immigration from foreigners with skill in manufacturing chips will also allow firms to bring in workers with valuable hands-on experience. Organizations in the US like the Economic Innovation Group have crafted proposals to allow for semiconductor industry–specific immigration reform. As other countries such as Japan raise immigration thresholds to attract skilled global talent, the US ought to enact such reforms as well.

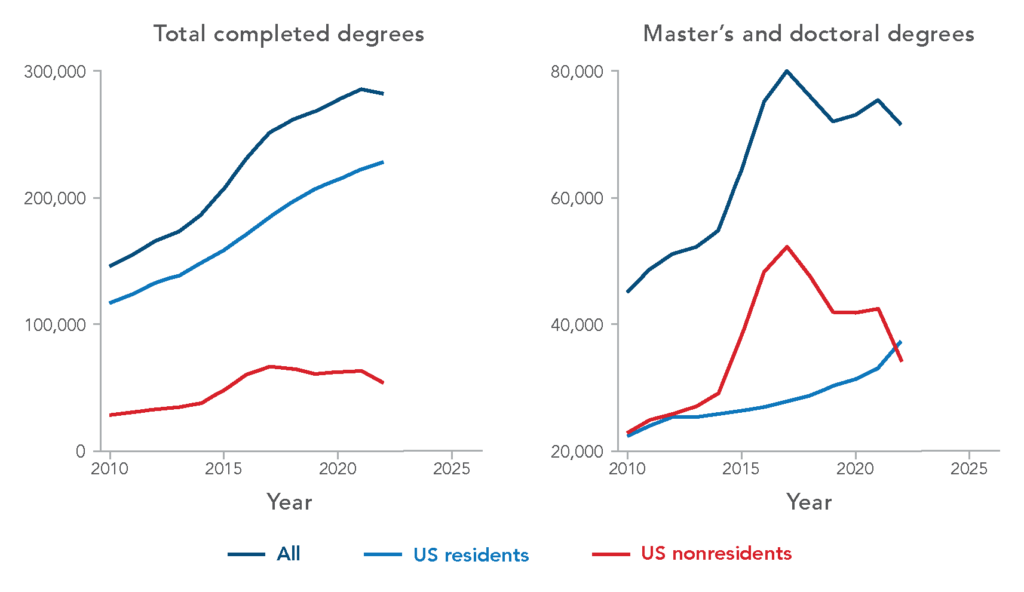

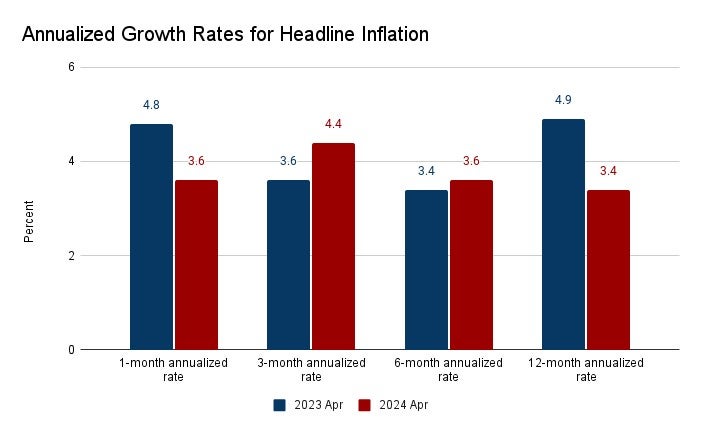

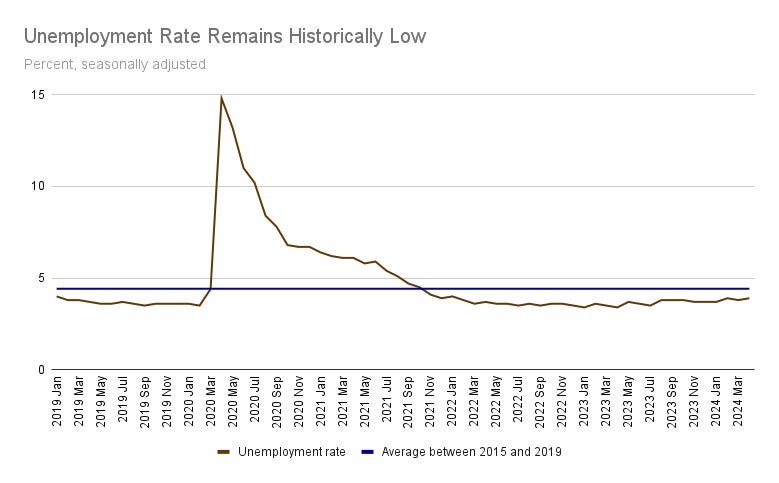

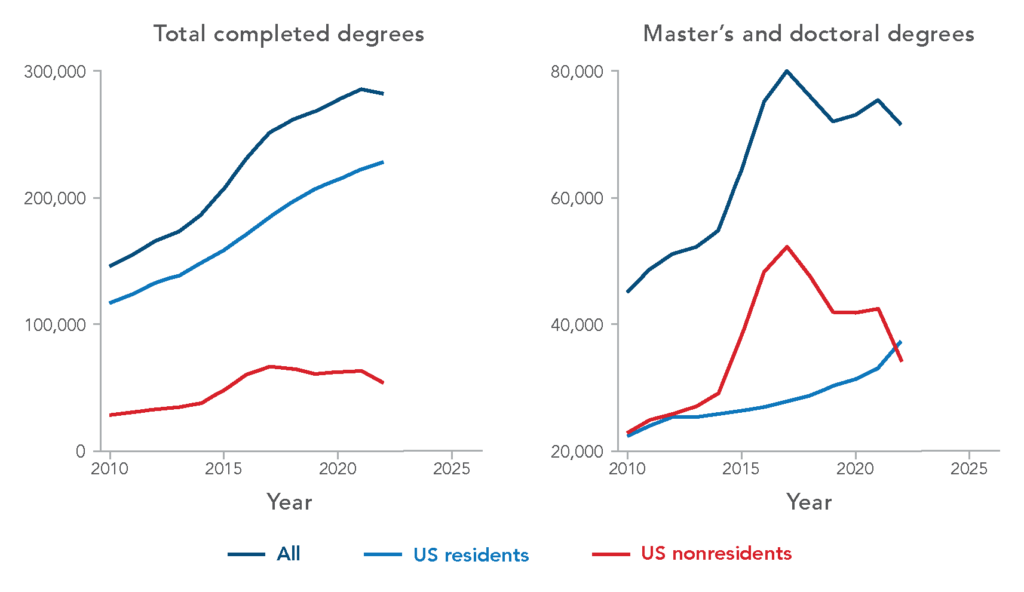

Such reforms to the immigration system are more important because fewer students are graduating from US higher-education institutions prepared for work in the semiconductor industry. As shown in figure 3, growth in the number of US graduates with degrees in semiconductor-related fields, such as materials science, physics, chemistry, and computer science (as defined by CSET), has stalled out recently. In fact, from 2021 to 2022, the total number of degrees conferred in these fields fell from roughly 286,000 to 282,000. Looking just at advanced degrees, the trend is even more alarming: among master’s and doctoral graduates, the US has been on a decline since 2017.

Both the total decline and the drop in advanced degrees have been driven by the sharp decrease in the number of nonresident US students, many of whom typically stay in the US on work visas after graduation. Just over 18,000 fewer nonresidents completed doctoral degrees in semiconductor-related fields in the US in 2022 than did at the peak in 2017.

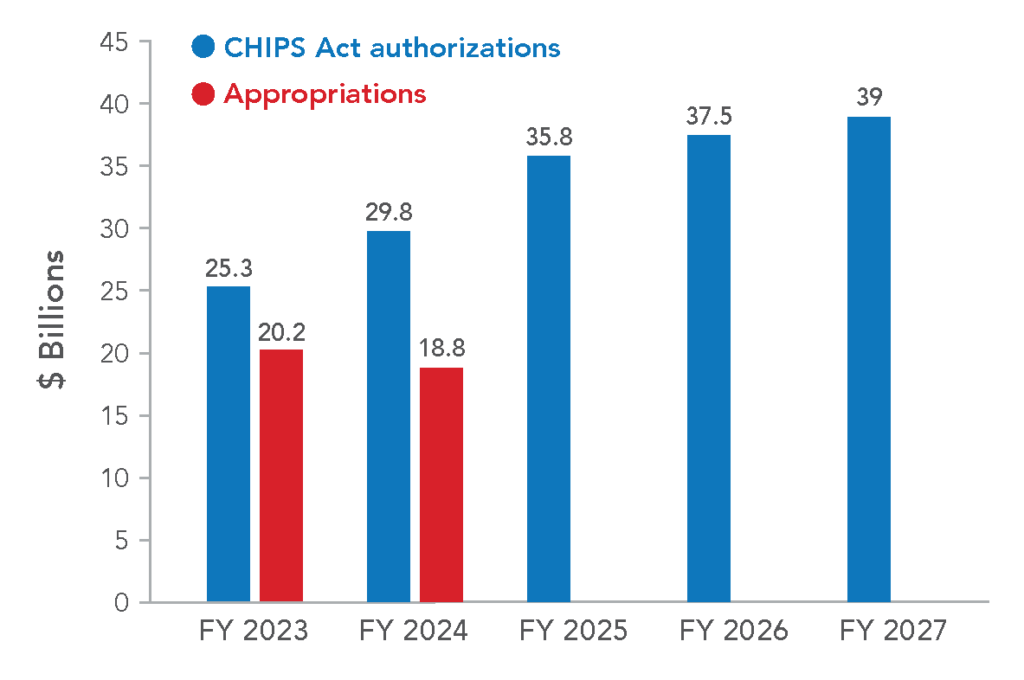

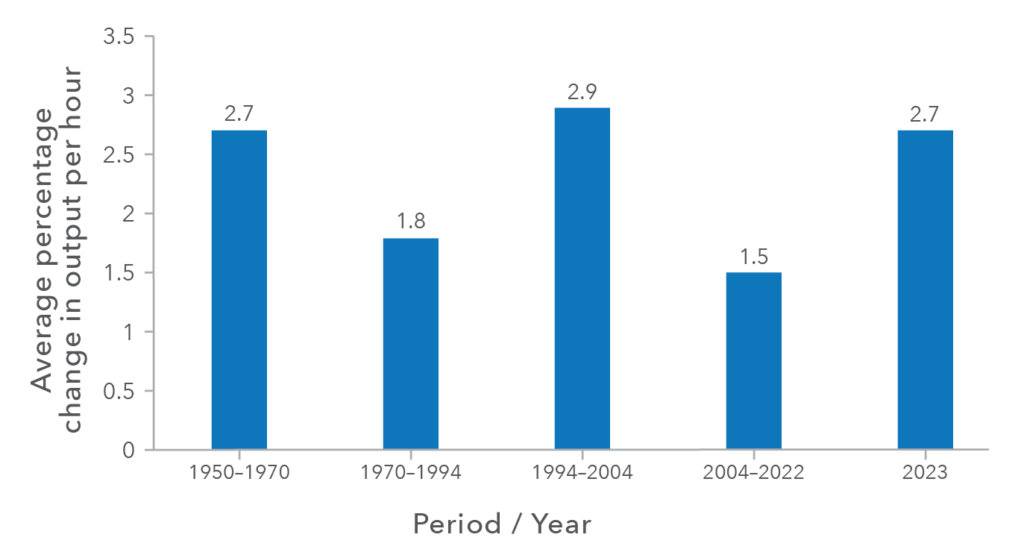

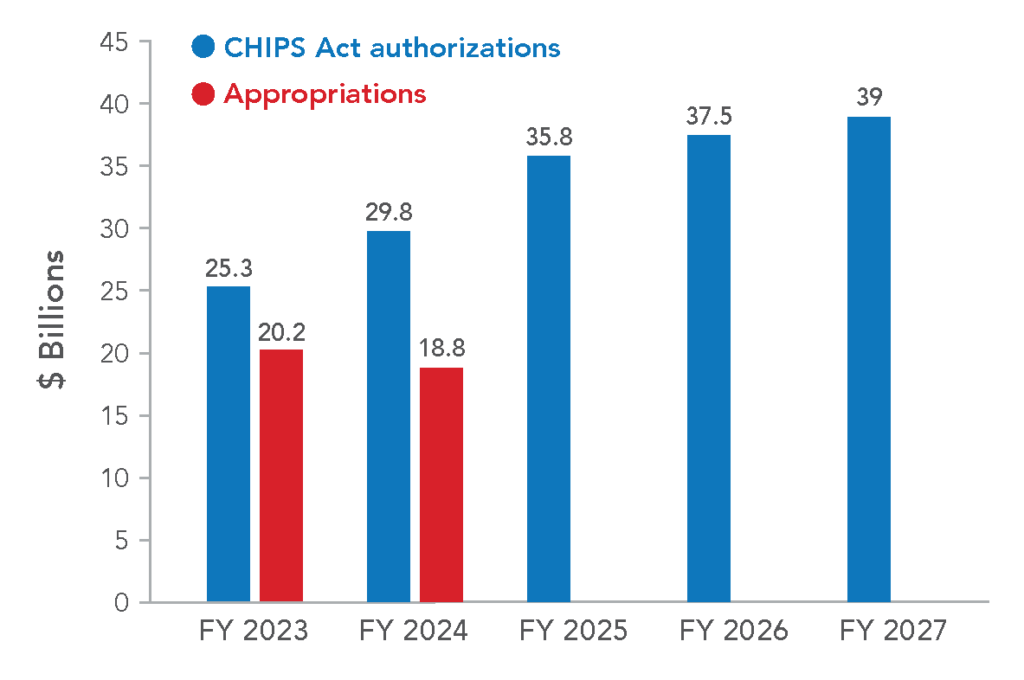

To build a skilled talent pipeline across all education levels, policymakers should follow through on investments in the CHIPS and Science Act. The law authorized $174 billion in spending over five years to STEM workforce development and R & D through several agencies—including an $81 billion increase in funding to the National Science Foundation (NSF). Unfortunately, these increases have not come through in recent spending packages: appropriations across these agencies for 2024 were $10 billion lower than the CHIPS and Science Act authorized, and in fact they cut the NSF budget.

Figure 3: Degrees in semiconductor-related fields have leveled out in the US

Source: Awards and degrees conferred by program and degree level at US institutions from Integrated Post-Secondary Education Data System (2022).

Note: Semiconductor-related programs are defined in Hunt and Zwetsloot (2020a). The data underlying this graph can be downloaded here.

Figure 4: Actual spending on STEM programs has lagged behind CHIPS Act funding

Source: Mui (2024).

Note: Funding included for the National Science Foundation, the Department of Energy’s Office of Science, the National Institute of Standards and Technology, and the Economic Development Administration’s Tech Hubs program.

Skilled workers will be more in-demand as other measures aimed at bolstering America’s advanced manufacturing capabilities take effect as well. The Inflation Reduction Act, for instance, includes $47.7 billion in funding for clean energy manufacturing, including producing advanced electric batteries domestically. A recent report by researchers at the Upjohn Institute estimated that employment in domestic lithium-ion battery production, another sector that requires advanced technical training, will grow by 247,000 by 2030. As demand for a skilled workforce rises—just as a result of the laws Congress has already passed—creating a skilled workforce will be critical to achieving these policy goals.

THE BOTTOM LINE

The nearly two-year-old effort to rebuild America’s semiconductor manufacturing capacity will soon move from the phase of announcing awards to getting money out the door and, ultimately, producing chips. Encouragingly, most public and private investments announced thus far are being made in highly skilled areas across the country, a sign that companies are taking the talent needs of this industry seriously. But policymakers are also failing to use this chance to build a more skilled workforce by facilitating greater high-skilled immigration and investing in the country’s domestic talent pipeline—steps that will also be useful as the US seeks to build independence in other advanced manufacturing industries.