Science and Innovation: The Under-Fueled Engine of Prosperity

Benjamin Jones (Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University) argues that the United States is vastly underinvesting in science and innovation, hindering productivity growth. He presents evidence that increased public spending on research and development would lead to improvements in standards of living and health, enhance our economic competitiveness, and advance our nation’s capacity to respond to crises.

Jones reviews the empirical evidence of the benefits of basic science investments and, drawing on the evidence, calls for three spheres of policy action:

- Scaling funding resources: Evidence suggests that doubling the total U.S. public investment in R&D would easily pay for itself through social benefits in excess of costs. Jones notes that a sustained doubling of all forms of R&D expenditure could raise U.S. productivity and real per- capita income growth rates by an additional 0.5 percentage points per year over a long time horizon.

- Scaling the people pipeline into science and innovation careers: Jones emphasizes that achieving the benefits of the science and innovation system will rely on having a robust science and innovation workforce—a process which requires long-term investment to cultivate individuals with relevant training and talent. In particular, he highlights the potential large returns from increasing domestic investment in STEM workers and importing talent through reforms to high-skill immigration policies.

- Making diverse investments: Risk is inherent to the innovative process. Instead of trying to pick “winners,” policymakers and the public must approach high-risk investments as making a wide portfolio of bets. This approach can produce more efficient search, lower collective risk, and increase returns in the science and innovation system. Public funding should push for diverse pathways instead of crowding into particular areas, and focus on increasing the scale of funding and human capital, and the diversity of approaches that are taken.

Finally, Jones cautions that policymakers should not become hamstrung over which policy levers to employ, such as R&D tax credits, funding the NIH, investments through DARPA. There is a need for more research about which channels feature the highest returns, but, Jones argues, the biggest failure would be to continue to underinvest, given the enormous social returns that could be gained.

SCIENCE AND INNOVATION AS A PUBLIC GOOD

Left to its own devices, the private market will underinvest in R&D. When one party engages in costly and risky work to discover a new idea, any discovery can be imitated and built upon by others, creating broader social value to the original work. The original innovator is unlikely to capture this broader social value, and the private value to the original innovator can fall far short of the social value it creates. As a result, private incentives to invest in creating a new idea may be well below the social interest in making that investment. This is the basic market failure and incentive problem that surrounds the advance of ideas.

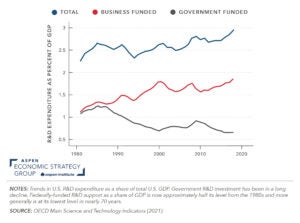

Public policy plays an important role in addressing this market failure by providing additional funding or incentives for R&D through a variety of mechanisms: government-sponsored research funding, intellectual property systems, research and development (R&D) tax credits, prizes, public research contracts, and advanced purchase commitments. Public funding for R&D investment as a share of US GDP is now at a 60-year low, as shown in Figure 1. This lack of investment is striking in light of recent and evolving challenges. The United States has faced a slowdown in productivity growth and rising concern about the international competitiveness of the U.S. workforce over many years, real wages for the median household have struggled to rise and have failed to keep pace with the gains in prior generations. Yet, as productivity has lagged, U.S. R&D intensity has slipped compared to other countries. In the mid-1990s, the United States was in the top five of countries globally in both total R&D expenditure as a share of GDP and public R&D expenditure as a share of GDP. Today, the United States ranks 10th and 14th in these metrics.

FIGURE 1: U.S. R&D SPENDING OVER TIME

THE EVIDENCE ON SCIENCE AND INNOVATION

Jones summarizes a large number of studies that estimate the social return to investment. He documents evidence on the very high social rates of return—in excess of 20% —found across agriculture, manufacturing, biomedical research, and in studies of the economy as a whole. In his own research conducted with Lawrence H. Summers of Harvard University, he finds the social rate of return to R&D expenditure in the U.S. economy appears to exceed 50%. Their analysis indicates that $1 invested in innovation produces, conservatively, at least $5 in social benefits on average—and quite possibly $10 or even $20 in social benefits per $1 spent.

COUNTERING THE SKEPTICS

Despite very high expected returns, the economic uncertainty and political risk inherent to federal investment in basic research have fueled skepticism about allocating scarce public funding to R&D. Innovative endeavors have a high failure rate. Since R&D is explicitly a search into unknown territory, judging success and failure ahead of time is difficult. And even when an idea is in hand, there is uncertainty about its future prospects, with eventual success often preceded by apparent failure. For every CRISPR breakthrough, there is also a Solyndra anecdote. Despite the risks involved, the evidence is abundantly clear: society reaps extremely large, long-run returns from public R&D investment.

Skeptics also question whether government officials have the capacity to identify and invest in good opportunities, or they question the value of experts themselves, who are often depicted as disengaged from “real-world” problems. Countering the skeptics of direct government funding, Jones documents the direct link between public funding and the public use of scientific research. Publicly-funded research has rich interfaces with public use, including for marketplace invention and government policy.

THE PEOPLE WHO DRIVE INNOVATION

A crucial driver of innovation are policies that advance human capital. Children exposed to innovators and entrepreneurs are more likely to become one themselves. In particular, girls who move to regions with higher shares of female inventors are more likely to become inventors. Importing talent through immigration is also critical. US immigrants patent more often than native-born Americans and make up a disproportionate share of the science and engineering workforce. Immigrants also account for a disproportionate share of entrepreneurs and are more likely to start companies of all sizes, including high-growth start-ups.

A VARIETY OF R&D POLICY LEVERS

There are myriad channels through which the federal government invests in R&D. For instance, DARPA invests in technology for national security, the tax code features R&D tax credits for private sector innovators, the NIH, Department of Energy, and the National Science Foundation fund research through a large network of national laboratories, research universities, and private-sector research contracts.

Large social returns to R&D are observed across all channels. It is less clear from the research which channels yield the highest returns. Jones cautions against allowing this uncertainty to lead to inaction altogether. While it is possible that such information would produce even higher returns, the true failure is not to put more resources toward R&D investment overall, which would lead to enormous positive returns.