Coverage Isn’t Care: An Abundance Agenda for Medicaid

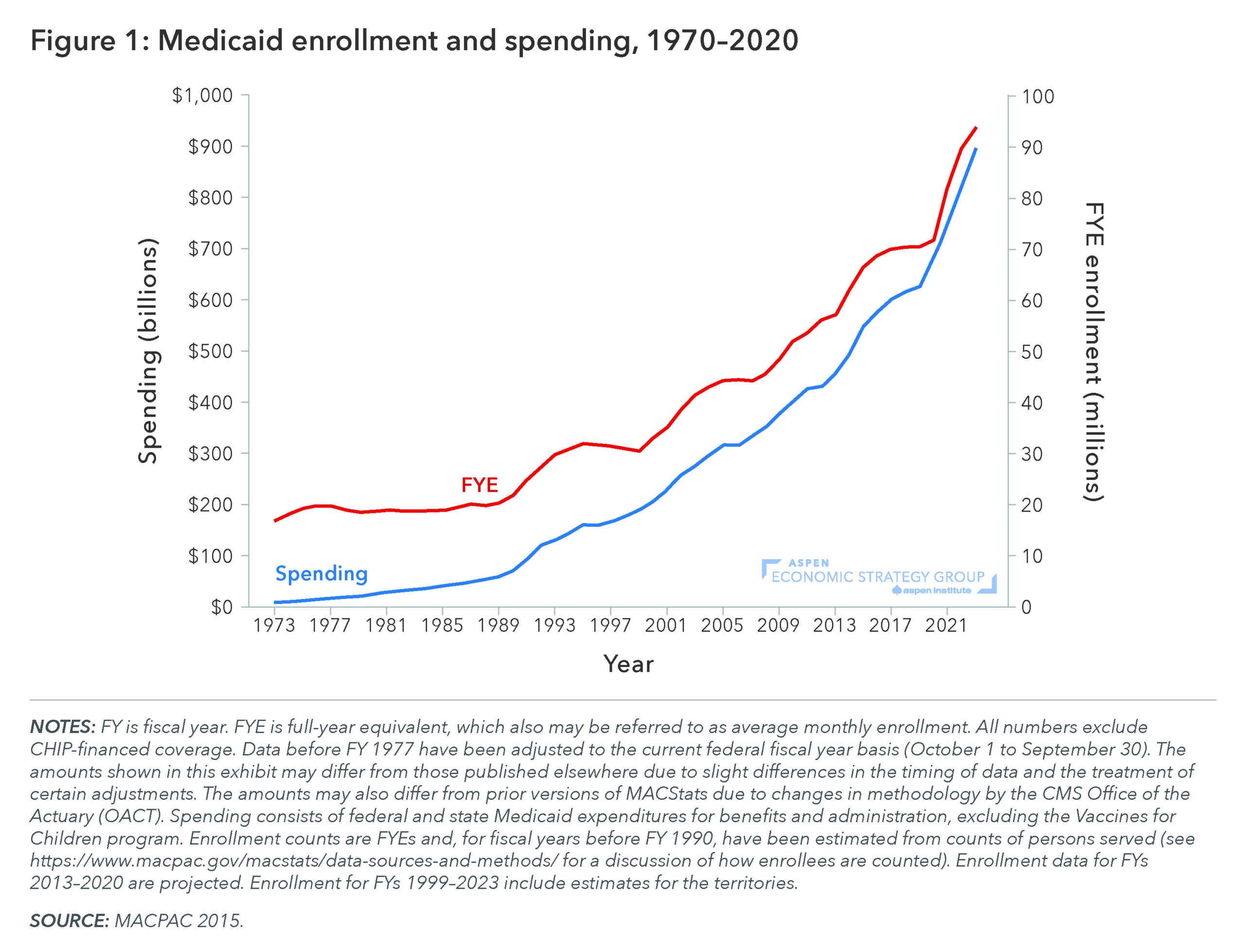

Originally a small, inexpensive safety-net program, Medicaid has grown into a major national health-insurance provider, covering nearly one in four Americans and more people than the public health insurance programs of the United Kingdom, Germany, or France. In Coverage Isn’t Care: An Abundance Agenda for Medicaid, Craig Garthwaite and Timothy Layton provide an overview of the Medicaid program; put forward a framework for thinking about the appropriate structure of the program; and propose a set of fundamental reforms aimed at improving the efficiency of the program.

The authors emphasize that decades of piecemeal changes have produced a fragmented program that merges various populations, providers, and revenue streams. They point out that recent reform proposals largely hold the structure of the program fixed and focus on marginal changes to financing and eligibility. Finally, they propose a broader and more fundamental set of reforms that acknowledge that Medicaid’s contemporary size and scope requires a different structure than its smaller historical predecessors.

Medicaid was created in 1965 as a small safety net program providing health insurance to the aged, blind, disabled, and very-low-income families with children. Eligibility expansions beginning in the 1990s set the stage for rapid growth. Congress first expanded eligibility to higher-income pregnant women and children (those with incomes under 133 percent of the Federal Poverty Line (FPL) for pregnant women and children under 6). In 1997 the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP, now just CHIP) was introduced. Through this program Congress offered matching funds to states to cover children in families with incomes higher than the national Medicaid eligibility levels. Many states set eligibility for children at 200 percent of the FPL. Finally, the 2010 Affordable Care Act extended coverage to all adults with incomes below 138 percent of the federal poverty line.

Medicaid’s costs are shared between states and the federal government. The federal government matches a portion of state Medicaid spending through a formula known as the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP), which varies from a 50 to roughly 90 percent federal match based on state per-capita income. As Medicaid was expanded to cover additional populations, Congress included more generous matching rates to incentivize states to undertake these expansions. The CHIP program included an “enhanced” FMAP for children in higher-income families with a minimum match of 65 percent. The FMAP was further expanded for the population covered under the ACA Medicaid expansion, which is almost entirely paid for with federal dollars (90 percent FMAP).

Garthwaite and Layton discuss the impact and feasibility of three commonly proposed categories of Medicaid reforms: FMAP reductions, administrative burdens and work requirements, and block grants and per-capita caps. All three, they point out, may generate substantial savings, but would almost certainly do so through reduced enrollment or by reducing program generosity (by, say, eliminating optional benefits like dental coverage), rather than creating a more efficient system.

The authors argue that instead of taking the current structure as given and trying to reform it with tweaks to the generosity of benefits or the level of enrollment, broader reforms are needed to expand the supply of a dedicated tier of lower-cost providers that offer access to basic healthcare for Medicaid patients.